|

THE BORSEY INHERITANCE by: Dr. John Wright

|

|

| Jim Borsey was born in Ashton-under-Lyme in

January 1920. He was the son of Percy and Jane Borsey. In 1939, at the

outbreak of WW2 he enlisted in the Manchester Regiment and eventually

became an armoury sergeant. In 1940 he was posted to Northern Ireland and

it was here that he met his future wife, Mary Ellen Wilson of Armagh. They

were married on 20th July 1942. Jim joined Wades Portadown in 1948, and

for about ten years he was employed as a tool-fitter, a job he

particularly enjoyed as it gave him the opportunity to use the practical

skills he had learnt in the army. Later, he moved to the turning shop and

eventually he was given the opportunity by Iris Carryer to use his

creative talents as a designer. In the late 1950s, Wade (Ulster) Ltd produced a very limited number of tea ware items in the ‘Armagh’ range. The range comprised of a teapot, cream and sugar. The pot was just over 6" high and of circular shape. The cream was 3½" high and the open sugar, a fraction over 2" high with a diameter of 4". The decoration was heavily influenced by ancient Irish art and consisted of alternating vertical stripes of circular Celtic motifs and open chainwork, separated by plain bands of ground colour. Covered with the characteristic blue/green/brown glaze of Wade’s Irish Porcelain, these rare pieces have become particularly sought after by collectors of Irish Wade. The teapot caries the Borsey signature on the base and though the other two items, the cream and sugar, are usually found without the name, there is no doubt that the entire range was designed by James Borsey. |

|

| Some authorities have attributed the range, the teapot in particular, to William (Bill) Harper the famous Doulton designer who, at this time, was employed by George Wade & Son Ltd, England. This would appear to be incorrect. Harper’s designs and models were almost exclusively of animals, birds and figures, not tea ware and in a conversation with the author, Bill had no recollection of having designed any teapots for Wade (Ulster). Moreover, the strong Celtic influence on the Armagh design is typical of Borsey at this time. Indeed, just a few years later, in the early 1960s, he was working on his celebrated Celtic Kells range. |

|

|

There is one other controversy connected with the ‘Armagh’ range tea ware; the Wade (Ulster) advertising material of the time makes no mention of the range and apparently no factory IP number was ever assigned to the individual items. This, again, has led to the speculation that the pieces were prototypes that never saw the production line. This theory would also seem to be incorrect for two reasons. Firstly, though there are certainly few examples to be found, they are extant in larger numbers than would be the case if they were prototypes. Secondly, the presence of Wade back stamps would suggest some sort of production run. Surviving examples of Wade (Ulster) prototypes, and there were some, do not usually carry marks at all. ‘Old hands’ who were employed in the Portadown pottery recollect the ‘Armagh’ nomenclature and confirm its production. It is possible that the name was used to designate the tea ware in the pre-production stage, but for some reason, it was later dropped. As Wade (Ulster) and later Wade (Ireland) did use Irish place names – Tyrone, Donegal, Killarney for example – it is a distinct possibility that ‘Armagh’ was a working designation, especially when the pottery was situated in the heart of the county and the back stamps of the period, emphasised the Armagh location. |

|

|

|

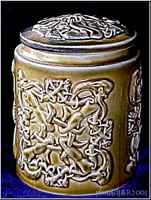

Borsey had always been interested in art, especially Irish art, and it was from this source that he drew design inspiration for the famous range of Celtic Irish Porcelain. Produced in the 1960s this range was characterised by a unique relief decoration incorporating a network of interlaced snakes, a motif he derived from the most celebrated of Irish illuminated manuscripts, the Books of Kells. Other examples in the Celtic range feature an equally complex arrangement of sinuous lines done in relief – those were known formally as ‘bread pullers’. The inspiration for this pattern was also to be found in early Irish sculpture and manuscripts. The ‘beard pullers’ was in essence a convoluted arrangement of arms, legs, hair and beards. The factory workers were less impressed by the ancient, cultural origins of the Celtic range and referred to it, not surprisingly, as the ‘the Knots pattern’. The vast majority of the pieces manufactured in Portadown were snapped up by Barney Lewis, the Dublin wholesaler, who exported them to the U.S.A., though some were also sold at Shannon Airport. The range was never a volume seller, nor was it envisaged as such, being made in limited numbers over a two year period. Only six shapes were produced, each prefixed by the letter CK for Celtic Kells. CK1 was a Serpent Jar, CK2 Serpent Dish, CK3 Large Serpent Urn, CK4 Beard Pullers Jar, CK5 Small Serpent Urn and CK6 Serpent Bowl. Each piece carried a moulded back stamp with the words ‘Celtic Porcelain by Wade Ireland’. |

| Jim Borsey was also responsible for the design of the Irish Porcelain Shamrock Range, first produced in the early 1960s. Apparently, the inspiration for this range came from Wade’s Irish wholesale distributors, Barney Lewis of Dublin, who put forward the idea that ‘something obviously Irish’ would be a commercial success, especially in Canada and the USA. Borsey rose to the challenge, and came up with the Donegal pattern – a large spray of sinuous, stylised, embossed shamrocks. The design was particularly pleasing to the eye and also to the touch. It was used primarily on tableware and included a cup, saucer, tea plate, sugar, cream jug and a preserve jar with lid. Some tea pots were also produced but in such small numbers that they are particularly difficult to find today. The moulded Wade back stamp for the range included a facsimile of James Borsey’s signature. |

|

|

The very popular Raindrop tableware range was another of Borsey’s designs. The pattern consisted of raised vertical flutes tapering out from top to bottom. To this day, former Wade employees refer to this decoration as the ‘teardrop pattern’, which was the original name used at the factory whilst the design was in its development stage. Obviously, the marketing manager was reluctant to use a name with such a negative connotation and the range was issued under the Raindrop label. Items available in this pattern included jugs, in three sizes, a coffee pot, tea pot, creamer, sugar and tea strainer. Like so many of his designs, the preparatory work involved was considerable, and, as he was the first to admit, the finished article had to be both aesthetically pleasing, yet amenable to economic production. Without his drive and enthusiasm, the Raindrop and other ranges of tableware would never have reached the retail market, for, as he once commented to a colleague, “The work involved is immense and the heartaches are many. You need to be both an engineer and an artist at the same time”. Jim Borsey certainly was. |

|

| In the 1960s, Wade was contracted by Goblin Ltd to manufacture the teapots for

their very popular ‘tea’s made’ product. Wade decided to spread the manufacture

of the teapots across the group, thus some were made in England and some in

Portadown. Jim did not particularly like the design of the pot he was sent from

England so he set about making it more aesthetically pleasing , at the same

time, ensuring that it was easy to make whilst retaining the insulation

qualities so essential for keeping the tea warm. Goblin was very pleased with

Borsey’s version but strangely enough continued to use also the original design

produced by Wade England. Though he enjoyed his job as a designer, Jim became increasingly frustrated with some of the restrictions imposed upon his creativity by the senior management in England. In 1968, he and a fellow entrepreneur, David Conlin, decided to start up their own pottery in Portadown. They rented premises in the Mourneview Street area of the town and working only in the evenings they began producing a range of giftware. They marketed their products under the name of ‘Armagh Pottery/Ceramics’. Unfortunately, the pottery was not a commercial success and folded after two years. |

|

|

|

During the Carryer period, 1947-64, Wade Portadown manufactured a range of ceramic tiles which they envisaged as being a runaway commercial success. Local photographer, Jim Lyttle, recollects an excited Major Carryer coming into his studio to have advertising photographs taken of the new products. At this time the Portadown Gas Works were building a new showroom in the town and Wade’s new ceramic tiles were chosen for the external cladding. This particular tile had a grey, granite- like appearance with the typical uneven finish of the natural stone. Jim Borsey was responsible for the development of the new product and had experimented with many different finishes. Brian Burns, an industrial chemist at Wade was a contemporary of Borsey, and remembers Jim using a hair dryer, a vacuum cleaner and powdered rock in his attempt to create the natural stone look on the ceramic tiles. Eileen Moore, supervisor in the casting shop, also remembered them well and recalled the great problem there was with making ‘L’ shaped corner pieces. Firing problems also caused a very high failure rate. Unfortunately, the tiles proved expensive to manufacture and the decision was taken to discontinue production. It is somewhat ironic that these cast tiles, which were a commercial failure, are still in place on the walls of the gas showroom, having withstood the vagaries of the weather for nearly 50 years - and look as pristine as the day they were made. |

|

Jim Borsey was nothing if not a gentleman. All his fellow

workers, who had the privilege of knowing him well, are united in their

praise. Essentially, a quiet, introspective man he shunned the limelight

of publicity. Iris Carryer remembers

him vividly, and recalls the great difficulty she had in persuading him to allow

his facsimile signature to be included on the Wade backstamp for the Irish

Porcelain range he designed. So high was her regard for his ability that she

even had the then Wade backstamp – ‘Irish Porcelain, Made in Ireland’ – enlarged

so that Borsey’s signature would be clearly legible. |

|